|

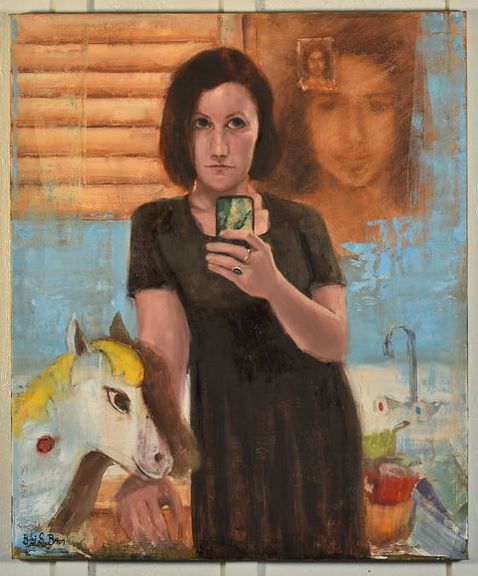

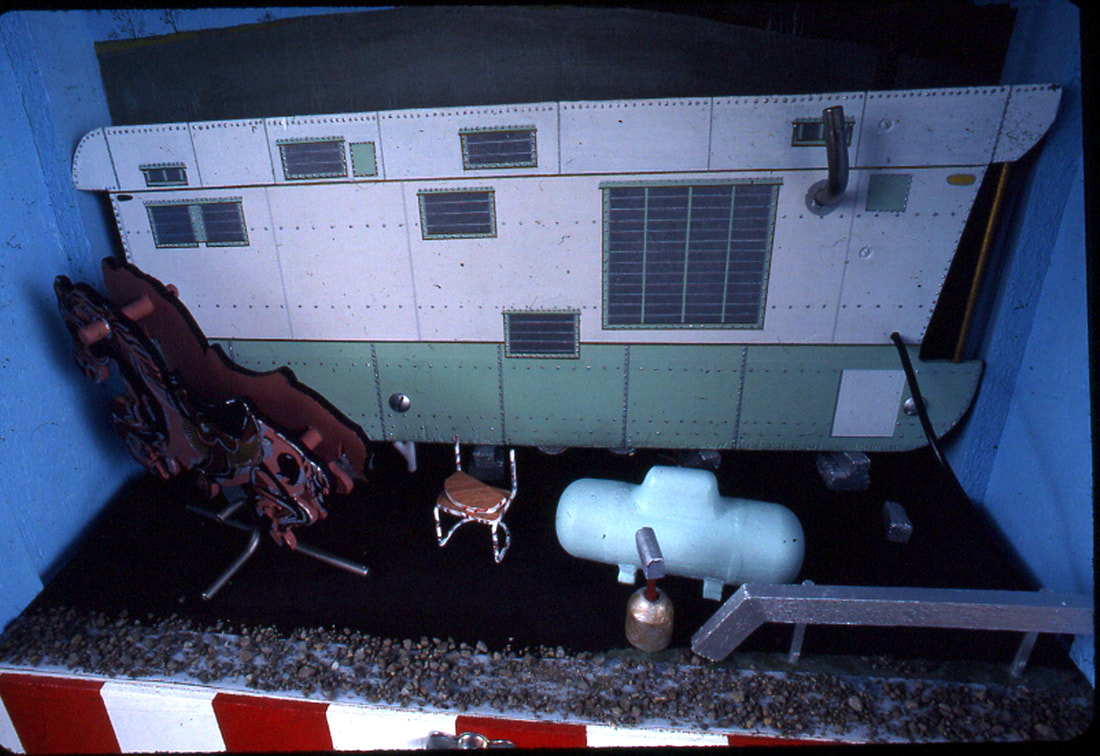

Not Camden "But I don't know that much about art." "C'mon, April, it'll be fun, there'll be wine and cute guys. We're not going to stay all night, it's just a place to get started. Besides, I thought you wanted to try something new." The weather was nice, being her namesake month, so the heavy winter coats were gone and that was liberating. Wine was good. The vote was still out on cute guys. "Ok, I can do a glass of wine." The gallery was pretty busy, a good crowd, mostly smartly dressed, a mix of money and hipsters. April and her friend Carmella didn't look out of place, though they belonged to neither of those groups. And the wine wasn't bad at all. Of course Carmella was off as soon as her hand closed around the wineglass, chirping, "Mingle, Dearie, don't be shy, its Friday night," over her shoulder as she disappeared into the crowd. April hung back, sipping and watching. She moved around the edge of the space looking first at the people, and then eventually the art. She didn't talk to anyone. There were large abstract canvases in bright colors in one grouping, small paintings of still lifes in dark colors in another. Big photographs of nude women in hats covered another wall; April didn't look directly at the nudes, but stared out of the corner of her eye. How were these women confident enough to pose like that? In another room were ceramics in earth-toned glazes, small bronzes of animals, and dioramas of mostly urban scenes. April looked at them as she walked and sipped her wine, stopping at the dioramas: an alleyway with trash cans, the back side of a building with a dilapidated fire escape, a street corner with a mailbox. It was like a doll house city, but she never really had dolls, not the nice ones anyway. The last vignette displayed a vintage aqua and white trailer home with a curious rocking horse, a broken chair and a propane tank. Urban scenes were fairly new to her, but she had seen trailer homes many, many times before. The trailer looked a lot like Mrs. Gibson's place. The one she grew up in was almost as old, though they would never have called it "vintage." The rocking horse was made of two flat, horse shaped cutouts, decorated in the style of the old animal cracker boxes, and straddling a seat on a spring. The back of the chrome and leather chair was broken and resting on the cushion. The louvered glass windows on the trailer were remarkable in their detail. Everything was very remarkable in its detail, and very familiar. April bent over, half empty wine glass in hand, and peered into the small louvered windows of the trailer. Those kinds of windows don't keep the cold out. Or the bugs in summer. She leaned in quite close. The interior of the trailer had the same level of detail: a tiny sink with dishes in it, tiny clothes strewn about, a tiny vase with tiny dead flowers in it. On the wall was a teeny tiny framed photograph of a young man with long dark hair. Like Camden. April stood up, suddenly dizzy. She took a sip of wine and slowly bent down to the trailer again. No, the guy in the photo wasn't Camden. She stared harder but the image was so small, and it was so dark in the interior of the trailer that she couldn't see it clearly. She put her wine glass on the floor and fumbled in her bag for her phone. Finding it, she looked around. No one seemed to be watching her, so she put the camera as close to the trailer window as she dared and quickly snapped a couple pictures with the flash, grabbed her wine off the floor and retreated into a corner. She opened the photos on her phone and studied them. The images were a little out of focus and bleached by the flash, but it was definitely not Camden. He was darker, exotic looking, at least where she was from. Maybe Italian, or Hispanic? Or Indian? Had she seen enough Indian people to know? He was shirtless, but his chest wasn't visible below the collarbones. Thick, wavy black hair falling to the bare shoulders was brushed back from a broad, smooth face. Smooth skin but bearded, maybe a couple week's worth. The lips were full and chiseled and curled at the corners in the faint smile. And the eyes under long arched eyebrows were kind. Definitely not Camden. She smiled back at the face on her phone. "Who's the dude?" hummed Carmella. "Jesus! Where did you come from!" shouted April. "Chill, girl, I'm just wondering who your new boyfriend is," Carmella said, looking around. "Is he here? Am I going to meet him?" she said with a laugh. "It's nothing, just an email from work." "It's Friday night, time to stop working, are you ready for the next stop?" "Sure, let's go," April said as she jammed the phone to the bottom of her bag, and they left. April came back to the gallery in the middle of the next week. This time she was the only person in the place aside from the saleswoman. She wandered over to the trailer diorama slowly, as if it wasn't her destination. She looked into the window. The tiny photo was still there. Why wouldn't it be? She quickly left. She came back several more times in the next couple weeks. She tried taking a few more pictures with her phone. The saleswoman, Justine, caught her one time. "I, I, just wanted, uh, a picture to, eh, show my, um, boyfriend." Justine started to tell her all about the artist and his processes, but April eyed the door. "How much is it?" asked April. It worked, Justine stopped talking for a moment to find the price sheet. She was back before April could reach the exit. "This piece is a steal at $1,500." April gasped. That was as much as a real trailer. Not a nice one, to be sure. "It's only going to go up once the artist gets famous, which will be any day now." Justine looked at April carefully. April looked away. "You can buy it on time, $300 down, $100 a month and it's yours in a year." It was May now. The winter hadn't been as cold as last year. It took some doing in a small apartment, but April made the space for it, near the window. She looked at the diorama. "I can't believe a bought a goddamned trailer." She peered into the tiny louvered window at the tiny image of the gently smiling, slightly exotic, bearded young man, whose kind eyes looked back at her. "You bought a piece of art," the voice softly said. By Marshall Hyde painting by Bibi Snelderwaard Brion

Made in a Trailer Park I remember the broken years you lived in that rumpled land submarine someone else had run aground at the park behind the drive-in. The faded green trim. The once upon a time white, a wind-buffed shade of bone. I remember how we would make up stories of all the lives given to it, lost to it, as if that dented trailer were a ship night-mangled on a reef of failed dreams, again and again, over the years before you and your mom pieced it together for your own doomed voyage, which seemed destined to leave you stranded there. I remember the way your mom rigged up that shower out back. Those three shivery buckets. The way you squealed from the cold, even in summertime. I remember the way she would rinse between double features. The glow from the giant screen filtered through the two small windows of your home, brightening her shoulders as if she did have stardust, as if she might have been a washed up, washed out, shooting star. I remember all those movies. The hollow sound of the tin roof beneath our feet as if the world might swallow us whole. The day that hail storm pinned you down for hours, as if trying to break through, trying to break you. I remember how you swore you’d get out. You’d wash your hands of that place, of that life. Here it is all these years later, someone else catching sight of you from that not quite collapsed abode. A girl, maybe, on the one-eared rocking horse you left behind, corralled in the stony yard. A mom, or dad, or aunt, maybe, looking up from a feeble kitchen chair plunked by the new water hookup, watching your massive face, that long ago ache in your eyes something you have turned to gold. No one even noticing the rotted corner of the big screen. Peeling layers of paint. All they see is the tear you have trained to run down your right cheek. As if you have channeled some part of you that never got out, that never truly got away. by Lafayette Wattles Video by Meg Willing

By Texas By Kansas, her neck sloped down to her shoulders as gently as the prairie rolled out and away from the road. By Oklahoma, her heart was a plateau she was ready to push everything over. By Texas her skin began to peel. She stopped for gas and almonds and sunscreen. She’d wanted it her whole life. She built it once when she was a child, and had been revising it in her mind until three days ago, when she signed over her Tercel as down payment. For that first draft, she’d collected wood scraps from the construction site next door – from the growing skeleton of a house that would soon harbor the freckled shit-wad who would publicize everything she wanted to keep from view, so that her life became a series of deeper and deeper retreats. Then, in a Dumpster behind the JoAnn’s, she found scraps of linen and burlap and vinyl that she used to cover the miniature windows, to upholster the tiny bench seat where she dreamed a real version of herself would read books while mountains rose up behind her, behind the glass. Always, she’d preferred gray days when the sky hung low and heavy, hemming her in. When she was twelve and needed x-rays of her mouth, they’d lain her on a table and spread a heavy smock across her body. She was disappointed the x-rays took only a couple of minutes. For the real Winnebago, an ’06 Voyage 34, she signed over her Tercel, and thought the chances were fifty-fifty that Jeremy would take care of the monthly payments as the statements arrived in the mail, until he heard from her. Did the hope in his brain make her love him more? The gas was cheap, the sunscreen was Banana Boat, and the almonds were dry-roasted. The boy who took her money had the same indestructability of her own son; she would have hated him before she became mother to a boy. Now all she had was her love and this other, aimless energy. The air outside was cool. The sky was wide and open and pink. The Winnebago ticked as it cooled itself and she counted off seconds between ticks to see if they occurred at regular intervals. Have the humility to learn from others. She did love her strange husband, who took so much more than he could ever see for granted. Her phone rang in the glove box. It hadn’t rung as much that day as it had the day before, or the day before that. And its tone had changed. She let it stop ringing then took it out of the glove box and turned it off. Either there were limits out there to catch her, or there weren’t. She watched the boy watching her through the window, though with the sunset reflected in the glass, there wasn’t much she could see about his face. by Meghan Gilliss Photos & installation by Willa Rose Vogel

Two Pictures Despite the elbowed exhaust pipe reaching for the sky on the outside of the trailer, the smell of bacon grease mixed with stale cigarettes hits the back of Cindy's throat the minute she walks in the door. Flimsy and crooked, the door swings out, and hangs opened behind her. She can see into every room from the doorway. No one is there. She takes three steps to the back wall and looks out the window above the frayed and flowered couch. But the backyard is deserted… Robbie's rocking-horse stands to one side, flanked by a broken stool. It feels like a sucker punch to the gut, how much she misses that kid in an instant. A few feet away, the welding torch sits on the ground abandoned next to a large metal storage tank. She thinks maybe that's a sign Ed will come back soon. But she can't stand the smell inside, so she walks back out the dilapidated door to sit on the cinderblock steps. She'll be able to see his truck the minute he turns on to the road. So if he doesn't want to talk to her, tough shit. He'll have to anyway. Ed shuffles along in the line of guys punching out. And like every other one of them, lights up a cigarette the minute he walks over the threshold. They grunt their goodbyes and fan across the parking lot, Ed in a beeline for his rusted out F-150. He doesn't bother locking it – who would steal this heap? But still, he's surprised to see the large yellow envelope on the seat. Left where he couldn't miss it. He picks it up, and swings himself in behind the steering wheel. He turns the sealed envelope over – but there are no markings on it. Still, he knows Cindy left it. Back in the good ol' days, Cindy used to leave him love notes, little presents – a handful of beef jerky sticks, once in a while a paper plate of brownies covered in aluminum foil. He always suspected the sweets were just her way of winning over Robbie. Ed rips open the seal, and finds an 8 x 10 photo. She's facing straight into the camera. But with eyes that seem to be looking inward, at her own thoughts, instead of at him. Her hair, her skin, her lips, all the color of honey. The image is nearly life-sized – just her head and strong shoulders – bare except for two flesh-toned spaghetti straps. Her hair is pulled back, but long loose strands frame her face like always. It looks like she posed in front of the blackboard in her classroom. He pictures her propping up the camera, then closing the door and taking off her sweater to stand there in her undershirt like that. He studies the way her one front tooth overlaps the other, just the tiniest bit, so that it almost shows between her slightly parted lips. And those pond green eyes, like summer calling to him after a long winter. She is daring him to still love her. And, the trouble is, he does. By Rhonda Morton by Christina Morris

**Special note: Sarah Foster chose to be both a writer AND a collaborator, so it made sense to layer these collaborations together as follows:

Megan Grumbling, writer + Sarah Foster, collaborator (dancer) Sarah Foster, writer + Simon Bjarning, collaborator (musician)

Starlight: A Choreographic Soliloquy

The essence of the dance is mint. The dancer enters, on finger-points, from above the trailer. A cool, shivery touch. Optimism and goosebump. Innuendo. The dancer’s fingers ever so lightly graze the surfaces – trailer, broken chair, rocking horse. A quivering bourée downstage. Peppermint, wintergreen. Starlight. Stella. Stella! The dancer gives a quivering shake. A beautiful, scintillating shudder. Like jazz hands. Like Pentecostalists seized with God. The shuddering is meant to express mint. The flash of her hands, palms open, Starlight. The sudden stoic whites of her eyes. Highway and Canyon. Her character lives in the trailer, waters the stones, checks the mail, paints peppermint stripes on the yard’s breakages and ends. Horizon. Her stoic whites of eyes, of course, are off-stage. The meta-proscenium. But it’s a distinction without a difference. Highway and Canyon. Off-stage, above the proscenium, the dancer widens her eyes. Horizon. Winks. That wink is not in the choreography. And yet it is true to the spirit. Mint. Optimism, innuendo, Highway. She is a good dancer. She can improvise. The dancer delicately spider-crawls up the trailer wall. And though the dancer has her choreography, the rules are loose. She has choice in her fingers. Even in her eyes. I've written it in, her choice. She can elect to wink. She is not a tiny dancer. She is quite tall, actually. Her hands in the yard. As tall as the trailer. When she reaches down into the yard, it is not like the hand of god; it is better: the hand of a dancer. The dancer improvises, with one finger, against the rocking horse. She does not ride the horse but rocks it. One finger. It conjures a certain kind of cowboy, a certain kind of yeoman farmer. Bootstraps, Fruited Plain. This choreographic theme is called Hope: The dancer stands two fingers on the chair and raises her pinkie and thumb. The dance is all about conjuring. Discovery. Optimism. See, how she checks the mailbox. With one finger, the dancer taps the mailbox, three times. Three times, like a knock. From her palm, magician-like, appears a small stone. She puts it with several others on the ground. She is building a wall with the stones. A sort of wall, anyway. Really she just waters them. But now it is tomorrow, and something changes in the dance: Today, no stone will come in the mail. The dancer taps the mailbox, reveals an empty flash of palm. Not a pebble, not even gravel. And the next day. Taps, flash-of-palm, empty. Beat. Again. Not even sand. Nothing to put in the wall. Nothing to water. Every day until now there's been a stone come in the mailbox. And so is it a kind of a political show I have choreographed, a political dance? How the stones keep arriving until they don't? The wall that is sort of a wall? How only one dancer can ride the rocking horse at a time, and even then, only with one finger? Both the stones and the dance seem so much smaller onstage. And bigger. The grandeur, the squalor. I’ve written dances for a lot of shows – music boxes, grange halls, but this one I can't quite get a handle on. Comedy or tragedy? You can't tell from the music; such a pastiche. Maybe it's not really a political dance at all. Maybe it's all about the body. The body in space. The dancer traces a finger up the stage-right wall, then leaps her palm to the far wall, clearing the horse. She dances it well, with abandon, minty ecstasy. Starlight Optimism. It's not easy. The syncopation, the compartmentalization. But it's beautiful, too, and when she hits it just right – the leap, clearing the horse, the gas tank, the grandeur, the squalor – stones or none, well, it just must feel so good in your body to pull off that kind of leap. And this set she’s leaping over, the setting of the dance. This trailer, that is. A trailer, wintergreen green. A symbol? A screen? A scrim? Perhaps the dancer herself is uncertain. Is the trailer a grotesque or an idol? Perhaps it is Schroedinger's trailer: Until you open it up, it is both. This choreographic theme is called Cognitive Dissonance. She moves on a line. On a point. Spins. Is she an electron? An angel? You can see from the candor of her dance that the dancer doesn't want to condescend to the trailer. She doesn't want to be precious. She doesn't want to use fairy dust. Everyone involved in the dance has had to contend with the problem of representation of the trailer. Is it a symbol? A scrim? A jack-in-the-box? The secret passage? A pasteboard mask? At some point, someone is going to have to knock on its door. The place I live, it's small too. Doesn't everyone live in a small place? It's called a body. A Body, this choreographic theme is called. The dancer moves at a slow 3. In a wave. This one, Society. She moves at a 6. In a writhe. This one, Grief. She moves at a 1. Limp. Her character has heard that the stones are really pebbles. That the stones are only gravel. That the stones are sand. Will the stones come again? The dancer holds her fingers poised near the mailbox, waiting for the next bit. I'm not sure I remember this next bit. The dancer starts to tap the mailbox, but hovers. Gives a quivering shake. Grazes the surfaces of trailer, broken chair, rocking horse. I have choreographed her movements. But she must dance them. Her fingers, her hands. Her lips, brows, eyes, high above the proscenium. The moon of the dance, so to speak. The stars. A kind of Starlight. A most beautiful light. Horizon. Even when it is only on a stage, only a dance. This whole show, truth be told, is more than a little hypothetical. A work in progress. Let's call it an experiment. Horizon. She widens her eyes. Tingling with spin, gravel, and mint. Optimism Like jazz hands seized. An unpredictable experiment. A knock on the door. But maybe, possibly, a great one. by Megan Grumbling The Dance is Mint from MoveWorks on Vimeo.

Reader: Douglas Milliken

Dancer: Sarah Foster

Original music, "Ours" by Simon Bjarning

in response to: Maybe I should just sit here. Maybe I should just wait for it to happen. I stop jumping. I mutter under my breath words I wouldn’t say in front of my mother. My not-so-carefully chosen clothing barely covers my thighs. I become acutely aware of a sticky film of sweat underneath my knees. Water starts to drizzle through, under the edge of the window grate. The overhead florescent lights flicker and make an intermittent buzzing noise. Like the sound of distant cicadas on a dewy night, somewhere in the South where the trees are bigger than they should be, with low hanging arms covered in lace. My arms feel heavy. I’m too lazy to hold them up. Maybe if I had done it differently. More determined - or from a different angle. This would have gone by faster. If wall clocks were still a thing, I’d watch the passing of the seconds. Every new moment eats up the past. Like a sewing needle poking through tough fabric, over and over again. Poke. Poke. Tick. Tock. But I don’t have a clock, just a ventilation pipe. My jaw tenses. I plunge my weight into the chair and push it to the corner. The back fell off months ago. That’s one of the reasons why I did what I did and why I’m doing what I’m doing. Too many broken things here. I tried to repair this sad little chair the way I repair everything - with candy cane striped tape and a good pun. I have many years of experience with inanimate objects - and the one thing that I know for sure is that they appreciate levity. Then I remember Pone, my beloved rocking horse. He sways reluctantly in the corner. His mechanical black eyes speak of many lives lived and his rusty joints squeal of abuse. I know he wants to know why we’re sinking. Why I allowed a perfectly fine mint and white motorhome to slide into my neighbor’s lake. Why I avoided Charlie and Yvette’s dinner invitations. Why I stole so many wrenches from the local hardware store. Why despite the tape, and the wrenches, and the jokes, and the fake repairs, we are still sinking. But it’s too soon to explain anything to anyone, especially a rocking horse. For all I know, we will be floating here forever in an endless circular river. I tell him, in my most caring voice, “don’t spell part backwards, Pone. It's a trap.” That’s one of his favorites. His laughter echoes against the outer walls, waves striking a tin roof. I read once, in a very smart-seeming book, that you can control your emotions by controlling your face. If I hosted a dinner party, that’s what I would talk about to entertain my guests. Then I’d make everyone at the table experiment with it. I’d tell everyone to make angry faces, and Charlie and Yvette’s brother would start screaming at each other. I’d tell everyone to make frowny sad faces, and Joelle would sink into her chair, watery-eyed. I’d order a chorus of hyena laughs and we’d all be best friends forever. I smile at the thought. I smile hard. And not just with my lips, but with my chin, and my eyes, and my teeth. Especially my teeth. To match my body to my face, I take a wrench in one hand and walk around the perimeter of the room, slapping my bare feet on the linoleum and lifting my knees high like a soldier. A joyous dance to match a joyous face. I bang the wrench on the hot water tank and I spin and hop and spin and hop. I shimmy left - I shimmy right. Joy boils in my flesh. Then the floor drops below me. The walls moan around me. I crouch down and back up against the wall. I drop the wrench. I insert my index fingers into the creases of my knees. I find comfort in the slick proximity of skin on skin. The small window by the ceiling has darkened. Water seeps in along the upper edges. A pool of liquid creeps up from the lowest part of the floor. I hear it coming. I wait. And smile. by Sarah Foster

BONUS! Sarah also brought a version of her writing with a short set of instructions for a willing volunteer to improv a short piece. Rhonda Morton (also a writer) volunteered:

I've Never Done This Before from MoveWorks on Vimeo. Skipper Madison Roberts had been trapped inside her sister’s camper since 1977. Emerging from the time warp required a period of reorientation to a world that had aged forty years in the flick of an eyelash. How had she gotten here? Barbie’s younger sister, Skipper made her own friends, Skooter and Ricky, because Barbie spent more time with Ken and grew more interested in making babies than babysitting her tween sister. That June in 1977 they had gone to the beach on Lake Michigan near Manitowoc and spent a weekend playing inside Barbie’s camper. Skipper, Skooter, Ricky, Ken and Barbie and their beachcomber recreational vehicle belonged to two sisters, Jane and Julie. As the elder sister, Jane had acquired her Barbie dolls new and Julie got her hand-me-down dolls when Jane was ready. When Jane and Julie went with their parents on a summer vacation to Wisconsin, they played in the sand dunes along the western shores of Lake Michigan. They brought their Barbie dolls and camper and dressed them in summer fun outfits and seated them around the formica table. Jane pulled back the draperies. Julie rolled up the window screens and let the summer breeze come through the mosquito netting. Jane laid Skipper on the sofa without putting an outfit on her. The midcentury modern design of blond wood cabinets and lineoleum floors gleamed in the bright sunshine. Julie and Jane went swimming, and for ice cream, rode their bikes with Skooter and Ricky in Julie’s pockets and Ken and Barbie in Jane’s. They forgot all about the camper and Skipper on the beach. Without realizing it, they left Michigan without picking up all their toys on the beach. Forty years later, Skipper woke up. Back in her body made of flesh and bones instead of molded plastic. She didn’t have any clothes on but her eyebrows were perfectly applied. Auburn hair hung to her shoulders. Perfectly shaped red lips. Bendable knees. Proportions of bust-waist-hips that weren’t like those of a fake Barbie doll. She was a real woman. In a trailer park filled with other midcentury pre-manufactured ticky tacky homes in a row. by Jill Swenson by Alanna Newkirk

Zoo I feel so small. Like a monkey in a cage. Like some extinct creature in a museum diorama. A passenger pigeon, a dodo, maybe a little sea mink cowering in a corner next to an extinct fern. I could make friends with that chubby pupfish over there. Or eat him. But I’m not. I’m human. At least the last time I looked. A human woman. This brief clearing in the woods was a discovery. A tin shelter. Whom it belongs to I’ve no idea, there is no lock. When the bright light comes I quickly evacuate, to hide myself, usually in the river, underwater. I can swim a long way on one breath. What I’ll do come winter I have no idea. I am braiding a rope from found remnants. When it is long enough, I plan to attach it high in a tree notch so that I might pull myself up in the foliage, hauling my rope up after me. Yes, in winter a thick conifer. Perhaps. When they leave again there is often something edible left behind. I don’t know if this is their carelessness, or if it is meant for me. It is difficult to surmise motives. When, if, I consume this—well, of course I do—I leave any remnant clawed, any bit of tin crushed, as if it was one of my near neighbors who devoured it. Scattered by wolves, bears, foxes, raccoons; those coyote, my vigilant friends. As I have no clothing I appreciate the offerings of these familiars. A scrap of rabbit fur, the discovered remains of a ravaged deer. If they had meant me no harm, you would think they would not have left me naked. Soon my hair will grow longer, long enough to afford me warmth, protection. Often now, I have moved on. Searching for the way free. I follow the river, or deer paths that might lead to the edge, but the woodland only thickens. The bright light comes no matter where, both here and there. Sometimes I just circle back to the tin house. Perhaps they are still searching for me. I vow to not be found. by Karen Alpha painting by Edd Tokarz Harnas

Vignette for a Vignette She cursed as the twig cracked beneath her boot. The sound, nearly imperceptible to human ears, easily startled her quarry back into docility. The hreinin’s amenability served well for hunting and normal work but was not what she needed today. She cursed again as she trudged to find another vantage point to fade from the herds awareness. The gravel crunched and spat as she careened down the narrow road. Her father’s not quite anachronistic letter had found her, dragging her back into a life she had fought hard to leave behind. The tiny dilapidated trailer loomed in the tree line, smelling of molder and rot instead of roasting meat and mulled wine. The sleigh to the side, once one of her favorite of her father’s toys, lay in shambles. The letter, written with quill in a tight script, had given little indication as to what had caused him to abandon the trailer or the job, or why he needed her instead of one of her siblings. She began a quick mental assessment of the things she would need to repair the slay as her truck came to a halt. She squinted towards the herd as she pulled her hood tight against the wind. She no longer remembered if it had been days or weeks since she had moved from the spot, having no way to mark the passage of time. The herd had slowly forgotten her presence, gone back to playing and fighting amongst themselves, digging through the snow for scraps of food below. She had had her eye on a spritely little doe for some time, hoping she would be the first. The little doe had a way of prancing and charging that kept even the adults on their toes. She could not keep a small smile from creeping towards the corners of her mouth as she watched the little doe thunder towards an aggressive buck. “You will be my Thunder”, she whispered to herself. The buck lowered his head to meet Thunder’s charge and the hunter’s trace of a smile turned into a full-blown grin. Instead of completing the charge Thunder leapt. And Thunder began to fly. by Joe Sanchez Portrait Thought to be of a Young Man as Hermes, God of Travelers, 21st century, color photo, American, Harnas School of American Photography, 2017. Soft lighting, enigmatic smile, long flowing hair emulates the contours of the figure; the shallow stage lends immediacy to view the beguiling figure. Photo of a Scene Thought to be Hermes’ Diary Room, still life diorama, American, Harnas School of American Crafts, 2017. Obscure lighting falls on a scrim shaped like the side of a camper and plays with the light and shadow over the objects of natural gas tank, oilcan, bench, and recliner. Hermes was known to travel around the globe in a camper, writing notes in a diary of his expeditions. Set in a shallow stage, viewers have immediate access to Hermes’ favorite writing lair. by Kathrine Page Ritual, felted stones, and traveling journal by Shannah Rabado Warwick

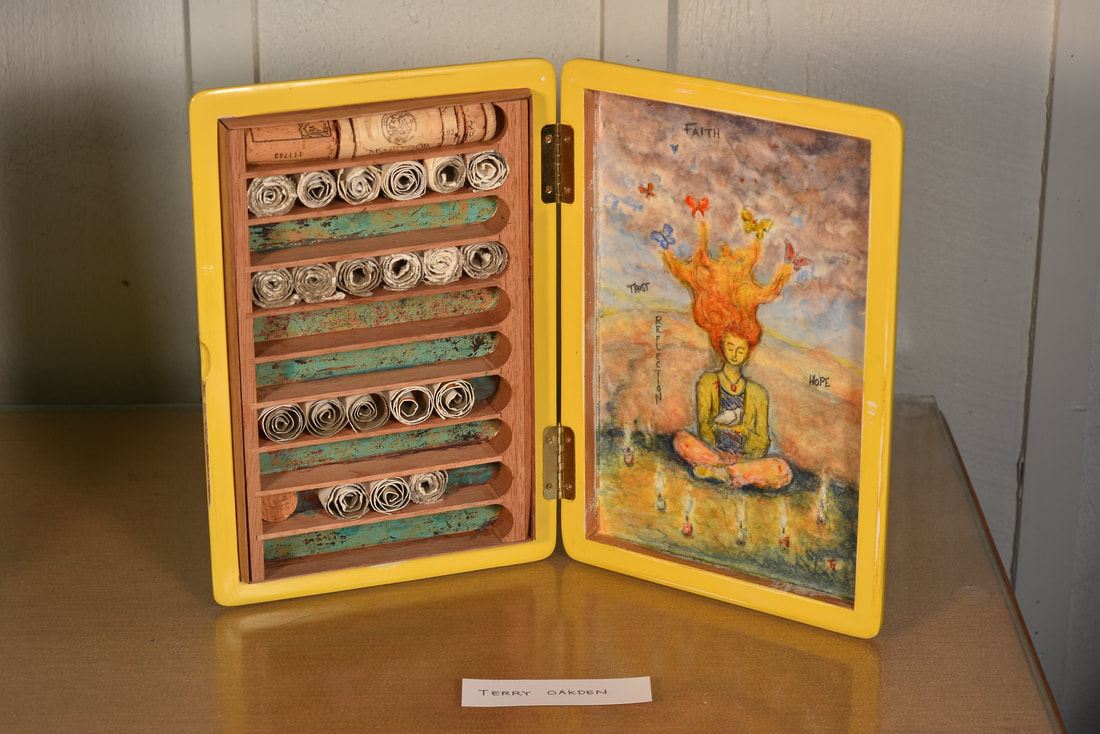

DAY 5 I made it! My first 20-mile day and I can barely feel my legs. A sip from the flask as a reward, but no fire tonight. It's not a busy campsite - one RV and a cook pit too close to share. Not sure if anyone is home. Protein rice over the camp stove tonight and another chapter of "Finding Me." It was the first day that felt strange without social media - and still no reception. Maybe the neighbors will want to chat. DAY 6 I decided on a rest day. My legs were like jello this morning and the weather wasn't great. Windy but no rain. Probably overnight. No one came in or out of the RV - I even knocked to ask about the cook pit. No answer so I used it anyway. Almond butter tastes better on toast. Feeling strong again and ready to hike in the morning. DAY 7 Crazy storm last night! A branch fell - missed me but not my tent. I pounded on the RV and no one answered. I let myself in. It wasn't locked and I wasn't safe outside. The RV was neatly abandoned. Someone left not long before I first arrived. The food and water, gone. Photos, journals, books, and decorations still in place. It was an intentional disappearance; an entire life left behind. Not forgotten, but gone forever. What I saw in the RV is no indication of who walked away from it all. I hope I meet her. By Sean Lukasik mixed media piece by Terry Oakden

Twilight at Dawn 1. Late Night Letter Jay, you know I never watched the news —Afghanistan, Iraq, I couldn’t point either out-- so when you went, it’s like you were lost. Or no, it was like I couldn’t follow. No, I was lost. I can’t write it all in one place so I spread it out and know it less. Do you think your mother thinks I’m dead? Even if she’d give them to me, any stars of yours would be dark-- dark stars are useless. I want to shine. 2. At the Laundry Heavy load of sweatshirts and stuff rolls up; eventually though, they tumble, the basket turning, working and working just to dry the clothes. And I watch the whole pointless cycle start again. Then it stops, jeans soaked. No more quarters. I never have enough. They gave us grades all through school-- math, social studies, even gym. I mean, there’s got to be a way to know, now, as adults, if you’re doing it right. Even how straight our letters were got grades. 3. Another Letter We had extra-curricular priorities, you and I; Elle’s almost twelve, proof of that. We had to hide from your mother back then; even now, she can’t seem to find me. Reality star, Elle says. Or some days, Engineer for NASA. So I’m taking classes on loans I might not ever be able to pay back. Now I get what a thesis is, and I’m learning elementary algebra. And what I’m made of. We do homework in sync, mother and daughter, each in silence, becoming what we can’t yet know. 4. Cleaning Up and Homing In The laundry’s in its basket still, days later; heaped up junk mail layers the kitchen table. Elle’s shoes make walking the hall a hazard. Yelling does no good. I begin with the clothes then work my way back to the table. Then sit. Objects finding their place eases me, even if order’s hard to achieve and doesn’t last long. Kitchen ready, I put on the pasta water. Home, the fact and feeling of it, is a softening I can make for Elle. It has to happen every day. Memories, mom used to say, won’t cook the sauce. 5. Starting Homework in the Gloaming I tower my textbooks against the window. Sunset’s long over, fireball gone, but above the black bulk of the hills yellow highlights the important edge. Gloaming, my new vocab, refers to being in-between. One word embodies many meanings. Twilight, on one hand, is darkness shouldering into day; on the other, light blooms on the stem of night-- betweenness means living the transition. You can’t trust words. So I start with math. Equations. Proofs. Let’s see what x is this time. 6. Last Late Night Letter In the small quite hours, I wake, and, magically, feel cozy in my trailer, in my life. Elle snores, but gently, the sound a comfort. Let me go, Jay. Let me live, and I’ll, I’ll, I will let you die. It’s been eleven years, eleven years, six months. Through my window a star I think is Venus gleams like a jewel. Night-time is becoming my friend again. Daylight’s no longer drudgery. I whisper Move on, move on, only partly to you. Embraced by star-shine, I snuggle in to sleep. by Edward Dougherty "Desperation" by Mary Weatherbee

|

66 OURS - Collaborative Writing ProjectStarting with Phase 1, writers had 66 days to base their writing on 1 anonymous person & 1 vignette, dutifully and judiciously assigned to each writer by Amelia. Photos given to the writersEach writer was given a combination of 1 person + 1 vignette from the following:

Person 1

Person 2

Person 3

Vignette 1

Vignette 2

Vignette 3

Categories

All

|