|

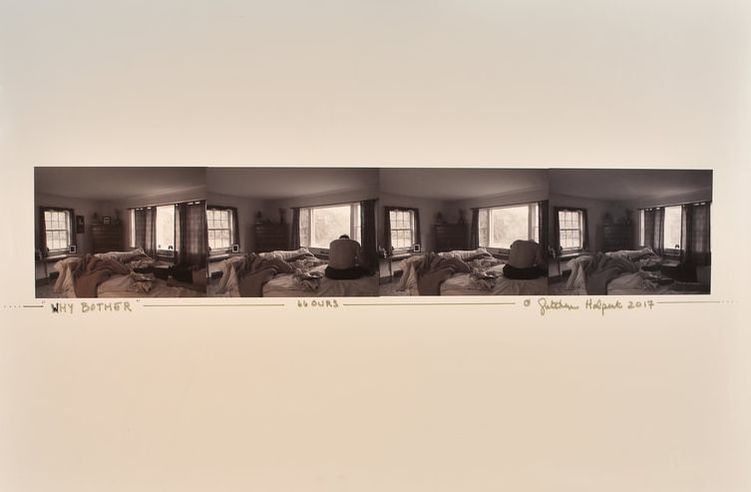

Michael Callahan hadn’t spent too much time figuring out what to do when he grew up. Why should he have? It made more sense to live day to day. How does anybody decide what to do with themselves? The canning factory closed in 2008 after the economy hit, so Michael was then out of his third job in a row. Time to give up? Not having anywhere in particular to be makes time go by fast and slow all at once. Have you ever tried it? Not just for a weekend, but a long stretch of time, weeks, months. TV gets dull. Really really dull. Michael found that even shows he would have called his favorite a year before had lost all their charm. Daytime court shows are straight insipid. Is there even any good TV anymore? He tried all kinds of sleep routines. Nocturnal like a raccoon, check. Are you familiar with polyphasic sleep? Did that. Sleeping sunset to sunrise. That one's better than you think. At this point, you're wondering how he survived, financially. Newton was a low-cost town. He got an unemployment check and completed the bare minimum to keep that up. His parents, a mile and a half from his spot, weren't willing to feed him dinner every night. But do you think they'd let him starve? No, of course not. And he wasn't 100% without work. The odd job came to him. That's why they're called odd, you know? Michael was surprised to find he liked house painting. It's boring, not particularly hard. It was all a paradox. A lot of decisions about doing nothing. Why bother showering? When should he make lunch? How much beer was too much for one evening? Whom should he call to hang out? What did he want to be doing, a week from now, a month from then, a year out? Is it okay to stay home for three straight days? How does anybody decide what to do with themselves? Would life be different if he won the lottery? (Should he play the lottery?) Do most people in his situation plan or just go with the flow? What are you doing today that matters for your tomorrow versus your next year? How do you be the best version of yourself in the worst situation? How much have you figured out? Are you prepared for changes? Are you prepared for no changes? By Neil Bardhan photograph by Gretchen Halpert

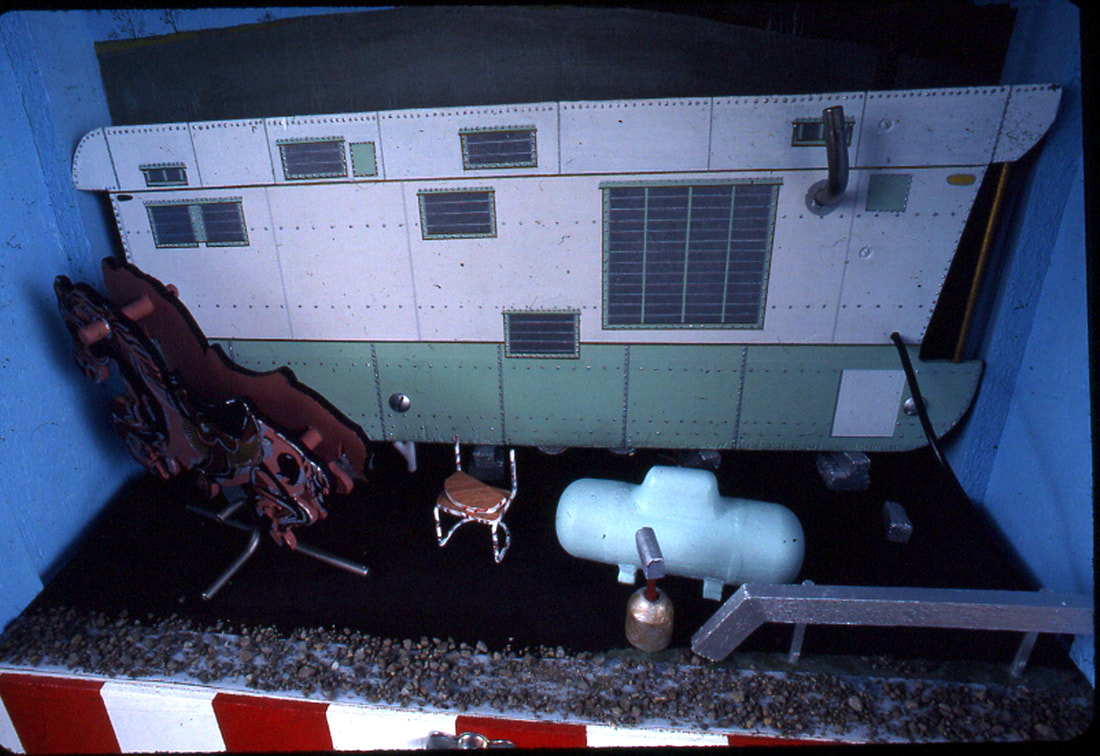

Hana, man, mona, mike; Barcelona, bona, strike; Hare, ware, frown, vanac; Harrico, warico, we wo, wac. I fell backwards from my fragile chair, not unusual for me, I fix things for a living so at home I like the freedom of disordered and broken things, I find comfort in it. I was never the goose on the playground, always the duck... like the kind of duck you see in the window of a Chinese deli in San Francisco hanging amongst brothers, it's not sad, each one is waiting to be freed from the hook, ready to become the antagonistic goose. As I lay there on my back looking up at the corrugated metallic horizon of my home It occurs to me... a tiger won't holler and a duck is no match for a goose. My story isn't sad, it's not even a story so much as a thought or the feeling you have when you play with your sibling jumping from chair to couch to chair, feet never touching the ground. You know all along that the lava makes it fun, you know that you can open the heat register and free your mini-figs from lego jail, you know that paper and scissor will never be a match for rock. I put the ashes in my pockets instead of the posies, my chair isn't broken because we all fall down. by Whitney Menzel video & choreography by Kristen Merritt

In Motion Monologue I can’t remember for the life of me, the last time I stayed put. By the time I was 10, I’d lived in 5 different homes. Seemingly nomad-like, I grew accustomed to a life of being on the move. Laying foundations one moment then uprooting the next. By the time I was 15, I’d become agitated if we’d been in one place for more than 2 years. Like an allergic reaction, I’d itch and get anxious and feel the walls closing in on me. It also didn’t help when Mum and Dad were racing up and down the stairs hollering at each other. Hollering? I put that lightly. More like full on screaming matches followed by objects hurtling through the air. I became so numb to it like background noise – a soundtrack to life per say. As long as I wasn’t directly involved, it wasn’t my problem. Having said that, it was inevitable that I’d become a direct target of my mother’s accusations and abuse especially when Dad had enough and crashed at my uncle’s place for 6 months straight before getting his own place. To say that period in life was a dark time is an understatement. It was perpetual, agonizing and plain confusing. Brainwashing is no joke and once you’ve reached the point where high school feels like the best 8 hour escape of your life per week, you really start to lose grip of what true joy is and start to question if you really are worthy of happiness. Fast forward 10 years, I’d somehow managed to climb up with hands on work experience, sorted myself a decent job with good pay, rented out a great apartment and had not spoken or seen my mother in 8 years by this point. I remember having nightmares and being flooded with guilt about not being able to withstand the physical beatings. I often told myself I’d chickened out. It just hurt too much both mentally and externally. There’s so much battering and bruising your psyche can take. You naturally burst and have enough. So, I left…just like that. I can say I’ve tasted momentary freedom a couple times to say the least. While naturally fleeting, there’s always a crash. Without guidance, the concept of freedom transcends into repression. Suddenly, you look around and see solid communities and friend’s families looking at you funny because you’re used to serving yourself first and putting others second. You are the only thing that matters to yourself – to keep surviving. Out of the rotating partners, fair weather friendships and hazy nights under the influence, the one thing I couldn’t shake off was not being able to stay put. I knew once the agitation and itching set in, it meant having to uproot yet again. I’ll never know where I’m heading in those moments but one thing I know for sure is to keep moving. By: Karina Curlewis performed by Ashley Wilson

Skipper Madison Roberts had been trapped inside her sister’s camper since 1977. Emerging from the time warp required a period of reorientation to a world that had aged forty years in the flick of an eyelash. How had she gotten here? Barbie’s younger sister, Skipper made her own friends, Skooter and Ricky, because Barbie spent more time with Ken and grew more interested in making babies than babysitting her tween sister. That June in 1977 they had gone to the beach on Lake Michigan near Manitowoc and spent a weekend playing inside Barbie’s camper. Skipper, Skooter, Ricky, Ken and Barbie and their beachcomber recreational vehicle belonged to two sisters, Jane and Julie. As the elder sister, Jane had acquired her Barbie dolls new and Julie got her hand-me-down dolls when Jane was ready. When Jane and Julie went with their parents on a summer vacation to Wisconsin, they played in the sand dunes along the western shores of Lake Michigan. They brought their Barbie dolls and camper and dressed them in summer fun outfits and seated them around the formica table. Jane pulled back the draperies. Julie rolled up the window screens and let the summer breeze come through the mosquito netting. Jane laid Skipper on the sofa without putting an outfit on her. The midcentury modern design of blond wood cabinets and lineoleum floors gleamed in the bright sunshine. Julie and Jane went swimming, and for ice cream, rode their bikes with Skooter and Ricky in Julie’s pockets and Ken and Barbie in Jane’s. They forgot all about the camper and Skipper on the beach. Without realizing it, they left Michigan without picking up all their toys on the beach. Forty years later, Skipper woke up. Back in her body made of flesh and bones instead of molded plastic. She didn’t have any clothes on but her eyebrows were perfectly applied. Auburn hair hung to her shoulders. Perfectly shaped red lips. Bendable knees. Proportions of bust-waist-hips that weren’t like those of a fake Barbie doll. She was a real woman. In a trailer park filled with other midcentury pre-manufactured ticky tacky homes in a row. by Jill Swenson by Alanna Newkirk

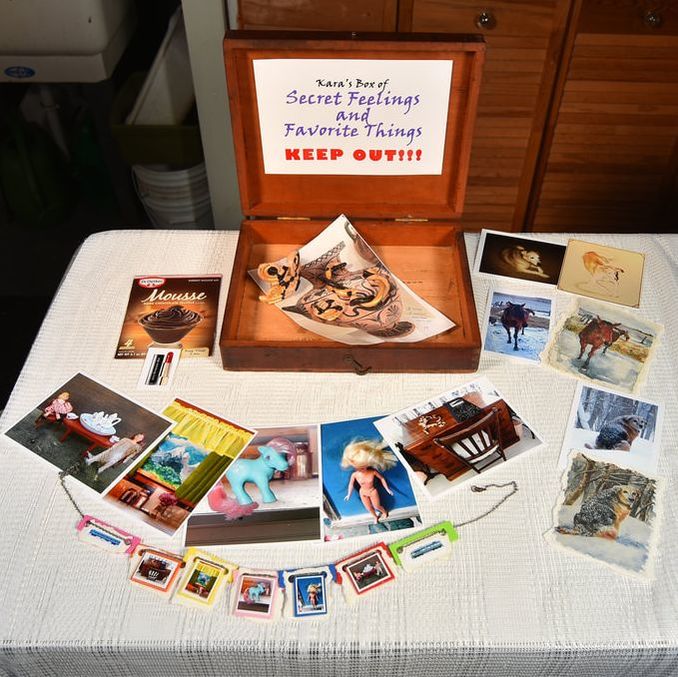

The Secret Life of Trains Janelle didn’t want to look down. As she half-smiled weakly at the faces peering up at her in shocked silence, she wondered why she always had her face on. It seemed completely unlikely under the circumstances that she would be fully made up, but she always was: brows filled in, undereye shadows scrupulously concealed, lips her usual shade of “Juicy Revolution Red.” The moment passed and the silence gave way to whispers and giggles. Soon it would be outright laughter among her classmates, resounding off the chalkboard that framed her torso. Another naked-in-front-of-the-classroom dream, Janelle thought. How original. She glanced down at the desk; this time, the report was on the recent discovery of ancient Etruscan pottery shards and their implications for modern reconstructions of the civilization’s demise. She sighed and gripped the report to her chest as she dashed for the door, assaulted by the tide of derisive hoots. ::::::::::::::::: Waking up was a relief when it happened. Janelle dimly remembered the naked dream, which had gone on to involve a horse and a dog and also, confusingly, chocolate mousse and someone named Kara. That name felt familiar. She heard it often, lately, echoing in her head. Was it outside her head, though? Something felt slippery about the name. But there was no one here called Kara. No one named Kara was on this train. There were plenty of things to wonder about the train: where it was going, who had chosen the terrible yellow color of the curtains, why the tables in the dining car were still Formica as if it hadn’t been updated since the 1970s. Janelle was sure that it wasn’t the 1970s, but there weren’t any calendars in the train to check. Perhaps the conductor had a calendar, but he was also a mystery. Janelle corrected herself: perhaps he or she had a calendar. She wondered the most about the scenery outside the windows: it faded a little with the days, and if you moved to a new car and a new window, it was different. But if you looked too closely out a window, you could see the tree-ish mountains not-moving very stolidly. They were not-moving all day, every day. They looked as if they were made of brushstrokes, or dots of ink from a stamp, but that wasn’t right. Janelle knew that scenery moved by, when one stood at the window of the train. And that landscape wasn’t made of paint. It couldn’t be right that they were not-moving. She unsnapped the clip holding the blind up and let it roll to the base of the window so the scenery could move or not-move on its own, out of sight. The main thing Janelle could do was to walk up or down the train and seek out the others. They weren’t always there, but she could often find Cleo or Pony or Eric hanging out in another car, passing the time. Sometimes they were having tea, or at least, sometimes they had a tea set. She got ready to start the day of walking. Walking and seeing the others was, so far, a lot more interesting than wondering about the train. They didn’t know any more than she did, but at least they moved more than the scenery outside the windows. And anyway, if she made it far enough down the train, she had other window scenes to look at, even if they were not-moving. No one else seemed worried about the scenery, but Janelle couldn’t quite forget about it. ::::::::::::::: It is strange to find yourself in a location other than the place where you fell asleep. But Janelle woke up in a different car, slumped over one of those Formica dining tables. She shook herself slightly, wondering if she’d had the naked dream again. What would a psychologist say?, she wondered. Always naked in front of everyone, and that girl named Kara again. Maybe I have a problem. There wasn’t a psychologist on the train. Janelle wasn’t sure why she knew about psychologists, but like the tea set and the dim sense of how scenery should behave, the knowledge seemed to have been a part of her forever. Yesterday, the others hadn’t been available. It was hard to say where they went when they weren’t in the other cars. Janelle wondered if sometimes, she wasn’t in any of the cars either. This was one of her least favorite things to wonder about; it made her mouth dry and interfered with her breathing. Wherever “there” was, outside the train, it seemed like a long way off. And how would she get there? Pony might know, but Pony was the hardest to talk to. Janelle wasn’t sure she was ready to wake up, after all. She settled her head back on the Formica; even the naked dream, which probably meant she was disturbed, was better than wondering what was outside the train or who was running it. She drifted quickly into the twilight of her sleep, where she realized once again: The whole class is staring at me. Why would they be staring? The giggles started to drift across the classroom. Not again. She tipped her head slowly to check. No shirt. She sighed. ::::::::::::::::: “Kara! It’s dessert! I’m not calling you again!” She fumbled with the doll’s clothes, trying to pull them off quickly so she could pull the pretty cherry-patterned dress on before she had to go downstairs. “Kara! NOW! I’m going to give your mousse to your sister!” “I’m comiiiiiiiiiiing!” she yelled back. She gave up on dressing the doll, propping her instead against the little slate chalkboard on her floor. “Sorry, Janelle,” Kara whispered. “I’ll be back soon. I’ll get you dressed up so you can look nice.” She scampered towards the door, glancing back at the toy train where her My Little Pony was standing on a tiny built-in Formica table while another doll was having a tea party with a half-cat, half-woman action figure she called Cleo. Kara smiled and shut the bedroom door behind her. by Tyler K. Cassidy-Heacock multimedia piece including necklace that was given to Tyler during the event in June

by Jennifer Green Fais Vignette for a Vignette She cursed as the twig cracked beneath her boot. The sound, nearly imperceptible to human ears, easily startled her quarry back into docility. The hreinin’s amenability served well for hunting and normal work but was not what she needed today. She cursed again as she trudged to find another vantage point to fade from the herds awareness. The gravel crunched and spat as she careened down the narrow road. Her father’s not quite anachronistic letter had found her, dragging her back into a life she had fought hard to leave behind. The tiny dilapidated trailer loomed in the tree line, smelling of molder and rot instead of roasting meat and mulled wine. The sleigh to the side, once one of her favorite of her father’s toys, lay in shambles. The letter, written with quill in a tight script, had given little indication as to what had caused him to abandon the trailer or the job, or why he needed her instead of one of her siblings. She began a quick mental assessment of the things she would need to repair the slay as her truck came to a halt. She squinted towards the herd as she pulled her hood tight against the wind. She no longer remembered if it had been days or weeks since she had moved from the spot, having no way to mark the passage of time. The herd had slowly forgotten her presence, gone back to playing and fighting amongst themselves, digging through the snow for scraps of food below. She had had her eye on a spritely little doe for some time, hoping she would be the first. The little doe had a way of prancing and charging that kept even the adults on their toes. She could not keep a small smile from creeping towards the corners of her mouth as she watched the little doe thunder towards an aggressive buck. “You will be my Thunder”, she whispered to herself. The buck lowered his head to meet Thunder’s charge and the hunter’s trace of a smile turned into a full-blown grin. Instead of completing the charge Thunder leapt. And Thunder began to fly. by Joe Sanchez Twilight at Dawn 1. Late Night Letter Jay, you know I never watched the news —Afghanistan, Iraq, I couldn’t point either out-- so when you went, it’s like you were lost. Or no, it was like I couldn’t follow. No, I was lost. I can’t write it all in one place so I spread it out and know it less. Do you think your mother thinks I’m dead? Even if she’d give them to me, any stars of yours would be dark-- dark stars are useless. I want to shine. 2. At the Laundry Heavy load of sweatshirts and stuff rolls up; eventually though, they tumble, the basket turning, working and working just to dry the clothes. And I watch the whole pointless cycle start again. Then it stops, jeans soaked. No more quarters. I never have enough. They gave us grades all through school-- math, social studies, even gym. I mean, there’s got to be a way to know, now, as adults, if you’re doing it right. Even how straight our letters were got grades. 3. Another Letter We had extra-curricular priorities, you and I; Elle’s almost twelve, proof of that. We had to hide from your mother back then; even now, she can’t seem to find me. Reality star, Elle says. Or some days, Engineer for NASA. So I’m taking classes on loans I might not ever be able to pay back. Now I get what a thesis is, and I’m learning elementary algebra. And what I’m made of. We do homework in sync, mother and daughter, each in silence, becoming what we can’t yet know. 4. Cleaning Up and Homing In The laundry’s in its basket still, days later; heaped up junk mail layers the kitchen table. Elle’s shoes make walking the hall a hazard. Yelling does no good. I begin with the clothes then work my way back to the table. Then sit. Objects finding their place eases me, even if order’s hard to achieve and doesn’t last long. Kitchen ready, I put on the pasta water. Home, the fact and feeling of it, is a softening I can make for Elle. It has to happen every day. Memories, mom used to say, won’t cook the sauce. 5. Starting Homework in the Gloaming I tower my textbooks against the window. Sunset’s long over, fireball gone, but above the black bulk of the hills yellow highlights the important edge. Gloaming, my new vocab, refers to being in-between. One word embodies many meanings. Twilight, on one hand, is darkness shouldering into day; on the other, light blooms on the stem of night-- betweenness means living the transition. You can’t trust words. So I start with math. Equations. Proofs. Let’s see what x is this time. 6. Last Late Night Letter In the small quite hours, I wake, and, magically, feel cozy in my trailer, in my life. Elle snores, but gently, the sound a comfort. Let me go, Jay. Let me live, and I’ll, I’ll, I will let you die. It’s been eleven years, eleven years, six months. Through my window a star I think is Venus gleams like a jewel. Night-time is becoming my friend again. Daylight’s no longer drudgery. I whisper Move on, move on, only partly to you. Embraced by star-shine, I snuggle in to sleep. by Edward Dougherty "Desperation" by Mary Weatherbee

She didn't know what she would find when she opened the box. Her memories of him, the old sage who passed along all of his knowledge, never seemed to own anything that would be this grand, this heavy, this full of potential and yet rife with memories of the overwhelming nature of his passing. He was not young, but also was not ready to leave this world; so many missed opportunities, stories, lessons on love and memories of her ancestors long gone. Her grandfather left her one simple thing in his will: “the contents of storage unit 55 at Al’s Cheap-Ass Storage, 1422 Rt 66, Chicago Illinois.” There she was, standing in front of the unit, which appeared to her a bit smaller than she imagined, opened to the setting sun with dust sparkling in the early spring light, and full of junk. Boxes of newspapers from 1950, Coke Cans held onto in the hope that one day they would be “antiques,” broken clocks that didn't appear to have any working components, even a few busted laptops. Then she noticed it. Sitting in the back corner, covered with a tattered sheet and fastened with the most glamorous bronze-plated locks that she had ever seen. It was huge, almost up to her chin, and appeared to have been cared for meticulously throughout his whole life. Next to it laid a note with her name written in calligraphed script. The note described his life as a travelling artist. He had a knack for voices and an incredible stage presence that once made Judy Garland spit her martini across the table. He explained his deep love for theatre and his desire to create sets out of his favorite family scenes, how he would mold the marionettes after the people he held most dear. As she opened the oversized box, she saw something magnificent. Inside was an exact replica of her favorite place on earth. His bar, where she had gone after school each day to wait for her dad to pick her up; where she had learned to love listening to his stories and those of his customers; where one time she had way too many Shirley Temples and threw up next to the regulars smoking cigarettes outside. The recreation was perfect, down to the exact detail. He had restored the drapes, a disgusting red and black that looked like they belonged as a coat on the little labridoodles from Mrs. Jensen next door. He had even perfected the first pinball game in the corner that she adored. It was spectacular. As she opened the box further, out fell two marionettes: one of an old man with grey hair and knowing eyes holding a cocktail shaker, and one of an wide-eyed young girl with blond hair and full smile. She was not sure what she would do with this miniature world full of memories and laughs, a place that was both the place where she both grew into womanhood and had her first beer and the place where she realized the true love a grandfather has for his granddaughter. She began to smile her dry smile, full of melancholy nostalgia. by Henry Powell Then, at that moment, the “Book of Dreams”, a book she found solace and comfort in, gently slipped from her lap to the floor.

She spent much of her time reading that book, since recognizing, in her teens, she had 'the gift', the gift of prescience. Before that revelation, she was regarded as a 'troubled child', who 'knew too much'. Hearing adults whispering about her caused her to retreat, to isolate herself from social contact. Some years went by. Her grandmother, who also had the 'gift', died. It was a natural course of events that she had subsequently come to live with her grandfather. 'Big Al', as he was known, quietly came into the shaded parlor. Picking up the book, he placed it on the stand next to her, along with a manila envelope-the number '55' scrawled on the front. locks & epilogue by Noel Sylvester |

66 OURS - Collaborative Writing ProjectStarting with Phase 1, writers had 66 days to base their writing on 1 anonymous person & 1 vignette, dutifully and judiciously assigned to each writer by Amelia. Photos given to the writersEach writer was given a combination of 1 person + 1 vignette from the following:

Person 1

Person 2

Person 3

Vignette 1

Vignette 2

Vignette 3

Categories

All

|